Inside National Parks

At the easternmost end of Big Bend National Park is Boquillas Canyon, remote and majestic, its limestone walls cradling the lazy Rio Grande. In the winter months, the river is between ten and twenty feet across and no more than a few feet deep. The hiking trail begins on the north bank, at the mouth, where a man erupts into a recognizable bolero each time hikers pass him, his booming voice amplified by the canyon walls. Several stones lie on the ground a few feet away, identifying him as “Singing Mexican Victor.” The Rio Grande is also the U.S.–Mexico border and Victor Valdez’s presence on the north bank is against U.S. law. He is one of the people described by the signage particular to the eastern end of the park, warning visitors that “purchase or possession of items obtained from Mexican Nationals is illegal. Illegally purchased items will be seized and violators may be prosecuted.” One needn’t see his passport to know that Valdez is not there to hike. Other Mexican nationals are there also, crossing the river on horseback or by boat countless times a day to collect “donations” that visitors are asked to leave in exchange for little metal scorpions, friendship bracelets, and walking sticks made on the Mexican side. The riders approach visitors, offering the privilege of photographing the horses and photographing oneself on the back of a horse.

Since these people pose no real threat, the relationship between them and the U.S. Border Patrol amounts to a daily, almost ritualized combination of avoidance, verbal reprimands, temporary compliance, predictable noncompliance, tolerance, and friendly exchange. This industry, if something on this small a scale may be called that, has been going on since early 2002, when the U.S. government ordered the closure of all unstaffed border crossings into Mexico and Canada. One of the crossings affected was that at Boquillas, which had traditionally served three purposes. For one, it had allowed park visitors to cross by boat and visit the rural village of Boquillas del Carmen in order to enjoy a taco and a beer and purchase some of these same souvenirs legally. Boquillas is the only crossing into Mexico from the grounds of a national park. The only other crossing within the forty-eight states is in Glacier, which borders Canada, where the border itself, high in the snow-covered Rockies, is significantly more difficult to cross illegally than this one. Since its closure, Boquillas residents have resorted to crossing the river many times a day in hopes of making a few dollars in the form of visitor donations. Valdez’s former job was bringing park visitors across the river, in the same boat that later served to get him to the north bank so that he could sing for money.

Secondly, and more importantly, like the other tiny villages along the border, Boquillas was sustained largely thanks to access to goods and services on the American side. Residents shopped at the campground grocery store at Rio Grande Village, the tourist center built in the late 1960s at a site which had been of human interest for centuries and was chosen by the National Park Service partly for its historical value. In the decades following, many Boquillas children attended school in nearby Study Butte–Terlingua. The closest Mexican town is Múzquiz, 250 km away, so going to town meant crossing the river to the American side. And thirdly, the crossing had been central to environmental restoration work on the Rio Grande and the surrounding desert and mountain ecosystems comprised in the land both north and south of the border. In 2006, four years after the border closure, protected wilderness areas on the Mexican side entered into Sister Park Partnership with the U.S. parks Big Bend, Guadalupe Mountains, and White Sands. From 2006 to 2013, collaborative restoration work on the river the countries share had to be conducted by means of “many hours of driving through Presidio-Ojinaga and Del Rio-Ciudad Acuña international crossings to work with counterparts.”

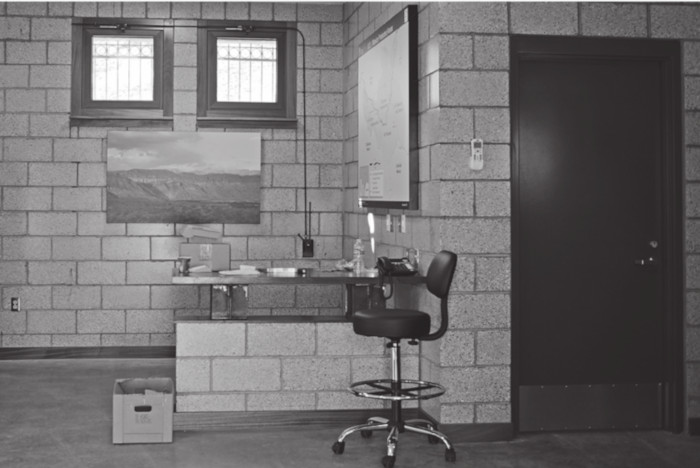

April 10, 2013, was the day of the long-awaited reopening of Boquillas Crossing Port of Entry, which had been announced and postponed multiple times over the two years prior. In this era of homeland security, the port of entry is “virtually staffed,” with a passport scanner and a camera that transmits the image to a staffed border crossing in El Paso, over 300 miles away. Prior to the closure the population of Boquillas was over twice what it is now. Many residents moved to the United States, where they worked without proper documents for years, and only some returned to their families and homes in Boquillas prior to the reopening. Valdez’s is among the twenty-five or so households left in the village, where literacy is low and passport applications difficult to come by, much less to fill out. Without passports, the Boquillas residents may not enter the United States. Once a two-way street, the crossing has reopened as a one-way street for the first time in the history of this region. The benefits of the reopening have been enormous from the perspective of binational conservation efforts, and collaborative wilderness restoration work is now much easier, in particular on the shared space that is the river. The National Park Service also benefits from advertising the cultural experience of visiting a real, honest-to-goodness Mexican village. The reopening is framed in terms of cultural preservation: since this region has historically always been binational, enjoying free mobility across the river, the reopening gives visitors the real experience that was not available while the border was closed. Not too far removed from the decision in 1930 to allow a handful of Ahwahnechee to remain on the grounds of Yosemite Park while others were forcibly removed, the value of the crossing is formulated in terms of visitors enjoying an authentic experience of the area and its cultural history. What the park’s interpretive materials leave out is that the unidirectional movement of traffic is a complete departure from the free movement of the past and is in fact creating conditions in Boquillas that are historically unique. The new crossing serves “American tourists seeking to experience a day trip” almost exclusively, while the Mexican nationals continue their northbound movements illegally. Valdez now sings on the Mexican side of the crossing for park visitors arriving by boat, while another man, who also identifies as “Singing Mexican Victor,” occasionally sings in the canyon on the American side, a sign that “Singing Mexican Victor” has become an institution. The flyer distributed in Study Butte–Terlingua alerting people to the reopening is clearly aimed at visitors more than residents. “Did you bring your passport? You should go to Boquillas!” it reads, and features a bulleted list of the new crossing rules under the heading, “Things to keep in mind”: a valid passport, a visa acquired on the Mexican side, customs regulations, and the crossing’s hours of operation. Among these points is the directive not to bring humanitarian aid items such as food and clothing to give to the villagers, and then another directive, more than slightly confusing in this context, in which First World ecotourism meets Third World desperation: “Have fun!”

Inside Panther Junction Visitor Center there is a panel that reads, “Who is the most dangerous animal in the desert?” It opens to reveal a mirror. What exactly is the sense of “the national” that the parks construct, and what modes of civic life are produced by this process? As they demarcate regions specifically designed to read as politically innocent, America’s national parks create particular social margins, in relation to particular social centers. It is this dynamic that I hope to outline in some detail. Who is the visitor in these spaces? Who is the national and who the foreigner? To whose children is the ostensibly unpeopled wilderness of the future owed, and at what cost (to whom)? In short, how is the contemporary idea of nation, in continuous tension with migration and indigenousness, reproduced in what counts as nature today? These are not empirical questions, but ones of political imagination.

* * *

Home

The National Park Service (henceforth NPS) website is decorated with the trademarked motto, “Experience your America.” Paradoxically, it is with the creation of the national park idea and the construction of wilderness as unpeopled space that this particular way of thinking about nature, as “yours,” emerges. The National Parks: America’s Best Idea, a six-part documentary by Ken Burns that aired on PBS in 2009, begins by emphasizing the collective “you,” a democratically organized body with equal rights to and equal investment in these spaces. “The national parks embody a radical idea, as uniquely American as the Declaration of Independence, born in the United States nearly a century after its creation. It is a truly democratic idea, that the magnificent natural wonders of the land should be available not to a privileged few, but to everyone.” This means not only that the parks are open to the public, with low entrance fees, but also that the public is directly involved in decision making. The NPS website has a “Planning, Environment, and Public Comment” link, with an extensive list of all currently active projects in the park system, from raising campground fees and fixing damage to park roads to comprehensive environmental management plans. Along with a relatively detailed project summary, each project page lists contact information for the park superintendent or project leader, links to PDFs of related documents, schedules of meetings about the proposed changes, and a page where users may enter comments directly during a limited open comment period. Accordingly, the Burns National Parks enterprise, which includes the six-episode documentary by Burns and Duncan and a coffee-table book by Duncan, also includes an elaborate PBS website with a “Share Your Story” feature, onto which users may upload text, photo, and video content to tell their own national park adventures to others.

Throughout the Burns series, the collective sense of “you” remains in tension with the first-person singular sense of “you.” A video clip with a voice-over by Burns’s writer and coproducer, Dayton Duncan, quickly turns the focus to the individual “you,” at the same time adding the element of “owner” of the park: “You, you, are the owner of some of the best seafront property this nation’s got. You own magnificent waterfalls. You own stunning views of mountains and stunning views of gorgeous canyons. They belong to you, they’re yours. And all that’s asked of you is to put it in your will for your children so they can have it too.” This intergenerational futurity is already written into the Organic Act of 1916, which establishes the purpose of the parks as being “to conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects and the wildlife therein and to provide for the enjoyment of the same in such manner and by such means as will leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

However, as philosopher and art historian Hubert Damisch writes, the actual purpose of the parks, “even today, is far from clear. . . . The periodic disputes over the national parks only underscore the contradictions implicit in their institution from their inception, contradictions that could not help but leave their mark on the very sites that the new agency had been charged with preserving.” Boquillas Crossing is precisely such a site of contradiction. Who is at home in this homeland, this space that is the river, at once wilderness and border? As people flock to national parks ostensibly seeking to leave home and to make contact with the Great Outdoors, they encounter spaces that are rigorously domesticated, landscaped, and tamed, not necessarily by design (although there is that too) but by deliberate discursive construction. The continuity between domesticity and wilderness that is the national park should come as no surprise if cultural theorist Dominic Pettman is correct in calling the parks “cartographic states of exception.” According to the vision of Frederick Law Olmsted, urban reformer, architect of New York’s Central Park, and advocate for the Yosemite wilderness and the park idea in general, these spaces were to be set aside for the contemplation of natural beauty by common citizens, especially the working class. In order for this to happen, however, Pettman writes, “this experience must be without any violent disjunction from the daily movements and rituals of urban or suburban life.” It is precisely because it is “yours” that the space of the national park cannot be so inaccessible or unintelligible as to seem threatening, foreign, or otherwise traumatic.

While city parks offer this continuity with home by virtue of their visibly unnatural designs, the vast spaces that national parks offer are tamed otherwise—ideologically and through the lens of the postcard industry and landscape photographers. For this reason, photography was central to the legal argument for the creation of the national park system. Photographs by Eadweard Muybridge, Carleton E. Watkins, and Charles Leander Weed offered support for the Olmsted Plan, which stated that the public had a right to Yosemite because natural scenery invites contemplation, that most universal of human activities which has beneficial effects on the society as a whole. At stake in 1865 was the universal, contemplative subject; thoughtfulness and civilized sentiments were no longer qualities exclusive of the elite. The supporting photographs offered “a reality . . . that is essentially ‘scenic.’” By the time of the drafting of the Organic Act of 1916, which created the park system, a magazine called National Geographic ran the “profusely illustrated” article “The Land of the Best” by the magazine’s editor, Gilbert H. Grosvenor. The article emphasized the scenery of the parks and the National Geographic Society put an issue in the hands of every Congress member before the act came up for vote. Today, the Yosemite website has a separate page dedicated to Ansel Adams, which announces that when the photographer (and by extension, every photographer since Adams) looked at the park, “he saw art.”

But the turn to the scenic predates the invention of photography by more than a century. The idea of private ownership of nature comes into existence at the same time as the idea of nature as scene, dating back to the rise of the bourgeoisie in the eighteenth century and the construction of private spaces for viewing nature appropriately. As explorers explored wild areas, they also created spaces where nature could be best appreciated and experienced by designating them with markers, describing them in guidebooks, and delineating them physically in increasingly rigorous mapmaking. The idea of rational land management extended to building equivalent natural spaces at home, often including aviaries and menageries of small, exotic animals, to serve as spaces for socializing. Thus, the idea of the natural park begins with eighteenth-century discourses around gardening, tourism, and rational and deliberate designing of environments for social interaction. National parks, however, mark a departure from the bourgeois idea of nature as a landscaped playground for nobles, by introducing the idea of democratic ownership. Modeled on the slightly different nineteenth-century concept of the city park, which belongs to every city dweller in principle, the national park presents the scene of nature for everyone to enjoy. In his writings, Olmsted specifically distinguishes the New World from the Old, where the aristocracy presumed that the working classes lacked the refinement necessary to appreciate either art or nature. “The free use of the land” by “the whole body of the people forever” is thus a political duty, part of the destiny of the New World and its break from Europe. Advances in technology in the 1850s made it possible for photographers to participate in Yosemite expeditions and present the public with a nature-scene, whose aesthetic value was beyond question. The twentieth century saw the democratization not only of nature as scene, but also of photography, so that democratic ownership meant that each visitor’s own, insignificant little camera mediated the experience of park space. Today, the right to contemplate the scenic means, famously, a handful of cars pulled over on the side of the road in Yellowstone wherever there is a moose, elk, or bison in “shooting” range. We almost never hike without our cameras, hoping for our own “Ansel Adams” moments. Signage inside parks often shows what is unmistakably a camera icon, indicating an upcoming photo opportunity, which thereby becomes a photo necessity. At the same time, since this imaginary is one of wilderness, we tend to take our park photos in such a way as to exclude the other cars, and indeed any signs of the other people. We make sure our photos of views, many of which we take at designated viewpoints constructed specifically for that purpose, exclude the very roads which brought us there. People, maintenance buildings, toilets, water fountains, trails, handrails, and anything else that recalls the infrastructure which makes our visit leisurely and, in some places, possible at all, is what we take great pains to exclude from the photographic frame. 16 The imaginary that is the national park depends on the maintenance of the democratic ideal in the photographic act, an activity related to both ownership and contemplation, and in the photographs themselves, which convey the paradoxical notion of a nature-for-the-people, at once “It’s mine” and “ It’s really, truly nature, with no (other) people in it.” The impossible simultaneity of these sentiments is necessary for the Great Outdoors to become both domesticated and democratic, “our” home from which we untiringly send postcards (to whom?) as if to say “wish you were here.”

But who, exactly, gets to be here, under what conditions, and with what caption? In Big Bend the relationships between ideas of nation, foreignness, and home are uniquely complicated, dynamic, and on display. Assumptions about belonging, security, and safety, expectations of surveillance and reporting, and even ecological concepts like native and invasive species are all inflected with the tensions particular to keeping undocumented Mexican migrants out. Prior to the reopening, the newsletter given to every visitor upon entry included a section about the border, showing a photograph of the very trinkets one was instructed not to purchase for multiple reasons: because the Mexican merchants will be arrested and, perhaps most importantly, because “supporting this illegal activity contributes to the continued damage along the Rio Grande, and jeopardizes the possibility of reopening the crossing in the future.” A separate section titled “Border Safety” instructed visitors to “avoid travel on well-used but unofficial ‘trails,’ “report any suspicious behavior to park staff or Border Patrol,” and not pick up hitchhikers. Those same safety regulations are in the new newsletter.

And yet ironically nothing happens on the surface. The tensions are present in precisely what one does not see. The border patrol checkpoints on both highways leading away from the park are in no way related to Victor Valdez and the Mexicans on horseback selling souvenirs, nor does the presence of this handful of people require increasing the number of border patrol officers in the park to eight, in accord with the general plans to increase border security along the entire length of the border. But something out there, somewhere, that abstract presence implied by the words “drug war,” requires these precautions and this infrastructure. In spite of a smattering of signs warning of thefts from unattended vehicles, visitors are well aware that “Singing Mexican Victor” is not a threat to border security, precisely because border patrol has bigger fish to fry. These bigger fish are not actually in the park itself, which boasts being the safest section of the border. The dangerous conflicts are taking place elsewhere, but their spectral presence informs the Big Bend landscape, both discursively and in terms of actual policies, which in turn affect the space in material ways.

Boquillas Crossing itself posed no danger for many decades, but the closure and the delay surrounding the reopening introduced a new climate, in which wilderness, apolitical by definition, and the ethics of restoration have become discursively and materially intertwined with the politics of homeland security. “Homeland” here refers to a threatened space that requires surveillance and protection, which becomes operative in what it means to maintain the park for future generations. Cooperation between the park service and border patrol, and the expectation that visitors will cooperate with both if it comes to that, shape a specific sense of the “everyone” to whom the natural space is imagined to collectively belong.

* * *

Visitor

In Death Valley National Park, the word “homeland” is in even more regular use. Here, the other national presence is the Timbisha Shoshone Tribe that has lived on the grounds of the park for centuries and claimed the right to continue doing so in the Homeland Act of 2000, signed six years after Death Valley National Monument gained national park status. The Timbisha Shoshone, and only they, have the right to live on park grounds, through which non-Timbisha U.S. citizens merely pass as “visitors.” The Furnace Creek Visitor Center houses a new exhibit, fully renovated in 2012, which underscores the distinction between who is at home here and who is merely visiting. A large plaque titled “Passing Through,” which refers to the area as being more suitable for visiting than for settling, hangs puzzlingly next to one of equally impressive size, titled “Homeland,” which describes the area as having been inhabited by the Timbisha Shoshone for thousands of years.

Death Valley is the only case in which the U.S. government has returned park land to its indigenous inhabitants. This is significant, since the parks from which Native Americans were displaced in the largest numbers were some of the earliest parks created—Yellowstone (1872), Yosemite (1890), and Glacier (1910)—while Death Valley is one of the nation’s youngest (1994). Much of the opposition to the Homeland Act was on the grounds that it would set a precedent according to which other tribes would demand the return of federally managed land. The newly redone welcome sign identifies the park as “home of the Timbisha Shoshone,” and the visitor’s guide that one receives upon entry lists the tribe as one of the park’s partners in wilderness restoration. In contrast to Big Bend, where “home” refers to America and not Mexico, in Death Valley “home” refers to Timbisha Shoshone land and not the United States. While the majority of visitors to Big Bend are Americans, due perhaps to its remote location (the closest international airport is a five-hour drive away), Death Valley’s proximity to Las Vegas and the Grand Canyon causes it to receive comparatively far more foreigners, especially Europeans. The exhibit at Furnace Creek includes a plaque titled “Identity: We Are Still Here,” which is clearly meant to appeal to the experiences and emotions of non-American visitors, describing the conflict between the Timbisha and the NPS as “familiar to anyone who has immigrated to another country—and to anyone whose country has been invaded and occupied.” It is not accidental that Theodore Catton, author of the Homeland Act’s officially commissioned administrative history, refers to the village at Furnace Creek as “the Tribe’s Sarajevo.”

The unique situation of tribe members living inside the park on reservation land gives rise to Death Valley’s particularly splintered historicity, which complicates the directive to preserve the land “for our children.” The different time scales on which park land may be imagined complicate the intertemporal ethics at work in the park idea. In Big Bend, for instance, the Panther Junction Visitor Center presents the landscape in terms of its prehistory, including extensive materials about dinosaurs that once lived there and focusing on geological information on an impressively large timescale. In contrast, Furnace Creek Visitor Center presents much of Death Valley’s history on the scale of its human inhabitants, including settlers, miners, and early vacationers, in addition to the prehistorical imaginary. But the Timbisha Shoshone’s presence frustrates the human historical trajectory. In “Seeing Death Valley,” the film that is shown in several park locations, tribal elder Pauline Esteves describes her people as having “always” lived there—a sense of “always” which is clearly incommensurable with a white-historical time line. And while busloads of tourists flock to the fully accessible Salt Creek exhibit in hopes of seeing the endangered, indigenous Salt Creek Pupfish in its natural habitat, the village, visible from the main road, with its smattering of mobile homes, remains mysterious, uncanny, and at a distance. Unlike the Yosemite Indians, and in some ways unlike the residents of Boquillas since the border reopening, the Timbisha’s role, at once ahistorical and contemporary, is not to enhance the visitor’s experience. Despite a very “Indian”-looking sign of turquoise and burnt orange, the village itself is not what Mark David Spence calls “the display of past-tense Indians.”

Privately, Esteves objects to the use of the term “tribe,” because she knows it to be politically loaded. She’s not talking about a tribe, she explains, but about the indigenous people who live on the land. And it was precisely because the land was removed from under their homes by the act of congress that turned Death Valley into federally managed land that the Timbisha became “non-ward Indians,” or Indians without official tribal status. Tribal recognition was necessary to receive government aid to continue living where they have always lived, and at the same time impossible, precisely because of where they lived. In 1983 the Timbisha became recognized as a tribe without a land base, which only made the quest for the land that much more urgent. Tribal government moved to Bishop, California, leaving behind two small, deserted administrative buildings and a defunct radio station in the village. The trust land on which the Timbisha are allowed to reside (including building privately owned homes with foundations) houses seventeen households today. Most of the inhabitants are elderly, because the young people have moved out of the park. As is clear in the distinction made by Esteves, however, the whole point was not to move. The community persisted thanks largely to a few individuals’ refusal to move out of their dilapidated homes.

The Homeland Act, an enormously significant event from the point of view of Native American law, deeply affecting the relationship between the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the Bureau of Land Management, and of the government-to-government relationship, was founded on the need of the tribe to continue living inside the park, not in the neighboring trust lands directly outside it.

The park newsletter includes a tiny map, presented under the heading “To Preserve a Way of Life,” which shows the large swath of land designated as “Timbisha Shoshone Historical and Cultural Preservation Area” to be most of the park itself. However, the village’s economic depression and dwindling population are caused in part by park-specific constraints on commercial development, as well as on the seasonal nomadism the tribe has traditionally practiced in order to survive the extreme climate changes. The mountainous area called “Wildrose,” the tribe’s camp during the sweltering summers, is no longer available for them as a place to live. As with the rest of the park, however, the Wildrose area is open for hiking and backcountry camping all year round, in keeping with the Wilderness Act of 1964, which defines wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man finds himself as a visitor who does not remain.” Far from trumping all else inside the parks, however, the Wilderness Act is in ongoing conflict with other acts of Congress—the Patriot Act in Big Bend, the Homeland Act in Death Valley, the Historic Preservation Act, and the Endangered Species Act—in competition with each other to govern park spaces in the terms specific to them. Often the terms of one act are in explicit conflict with those of another, and these tensions are among the main themes of this book.

Social inequalities, and the economic inequalities that both generate and result from them, exist inside national parks and not merely incidentally. But the ecological and aesthetic concerns at the heart of the park idea turn these into “cultural experiences” for the visitor, rendering them unintelligible in political terms. Much work has been devoted to showing that the depoliticization of wilderness has a history, but I am interested in the ways it remains pervasive today. One major reason these dynamics are difficult to see, much less resist, is the role of affect, or emotion, in the production of civic identities marked by a relationship to wilderness. I would like to begin to outline something we might call the wilderness affect, which includes, I argue, our participation in wilderness-as-spectacle as a form of social relation. I hope to show that any examination of wilderness must today also be an examination of mass society, specifically of the emotions surrounding collectivity. And finally, since environmental responsibility is presented in terms of obligations to future generations, my questions will concern the affective investment in the future in ecological discourse.

This, then, is a book about the foreigner and the future as they shape nature-spaces held in reserve for an unprecedentedly future oriented “us.” The two parks I study here, Big Bend and Death Valley, present these issues in particularly vivid ways. But beyond these case studies, how we imagine the foreigner and the future has already begun to impact the national park to come, shaping the national park system in general as it struggles to adapt to breathtakingly rapid social, economic, and ecological changes.

Photo: Jacqueline Schlossman

Photo: Jacqueline Schlossman

Photo: Jacqueline Schlossman

Photo: Jacqueline Schlossman

- Margret Grebowicz

Excerpts from The National Park To Come

(Stanford University Press, 2015)