The Ends of Desire

Existential ambitions are formulated in such extreme and simple language that they appear like human universals, immune to situation, history and material conditions. But they never arise in a cultural vacuum. Today the question why do this? is included in nearly every mountaineering narrative. Another popular recent climbing film, The Dawn Wall (2017), about Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s climb of the notoriously unclimbable Dawn Wall of El Cap, opens with the two men sitting in their portaledge and receiving a call from a NYT reporter. The reporter has two questions for them: “how are you?” and “why are you doing this?”

Rather than the climbers providing answers, it’s actually the HD footage in today’s climbing films that alone provides the kind of answers the public seems to accept. Perhaps the best example of this is Base (2017), a fictional story about BASE jumpers starring celebrity BASE jumper Alexander Polli, who died in a jumping accident before the film’s release. The story tracks his character, JC, through two jumping partnerships in which his partners both die, one after the other. Notably, the question why? does not figure much in this film, but this is because the GoPro footage — firmly built into BASE jumping culture — answers it a priori. This is especially heightened for the latest and most deadly variation of the sport, namely wingsuit BASE jumping, in which a sort of flying-squirrel- suit-like onesie allows the jumper to glide for long enough to simulate flight. Most of these GoPro videos are taken on jumps in spectacular wilderness locations, so that the human appears to be dipping low like a starling, playfully skimming the wild terrain. One video and you get it: because it’s that cool.

While why? doesn’t feature as strongly in Base as it does in other contemporary films, what does feature strongly is JC insistently asking his soon-to-be-dead partner, “Do you really want this? Do you want it? Do you?” He assures his partner that if indeed he really, really wants it, he’ll be able to do it. The authenticity of the desire is key to the physical ability — in order to do it, you have to really want it — so that the act and the desire ultimately become synonymous, as if desire itself were a kind of human flight.

.

Meanwhile, at the same time, the accomplished climber has come to stand for the apex of not only physical but professional, financial and social achievement — the winner standing on top of the world. So much corporate advertising signals that life, or at least what counts as “having a life,” is indistinguishable from “upward mobility,” but not only in the economic sense, not anymore. The image of climbing-as-success works to naturalize the relentless drive for more, as if amassing wealth were the most natural, obvious, spiritually and environmentally integrated thing to do. As if it were freedom itself.

The climber is the ideal figure of this, and not only as metaphor. A 2018 article with the provocative title “The Equation that Will Make You Better at Everything” argues that excellence in any domain requires the same stuff. It uses the image of the rock climber, as well as a certain narrative about the climber mindset, to help you to “grow your career,” “grow your team and organization,” and “grow your relationship.” It’s by the authors of Peak Performance (2017), a self-help book promising to deliver “the new science of success,” which argues that growth is growth, regardless of the activity, and begins from the assumption that growth is the only thing that counts as a goal.

Given these equivalencies, the old image of the climbing rat, as they are affectionately known, a kind of romantic, fit hobo obsessed with mountains rather than the traditional goals befitting a young man, is also disappearing:

"So what makes a highly paid fashion designer quit her job, buy a Eurovan and move to Kentucky to serve pizza and climb every day? What possesses an engineer to become a climbing guide? Why would a professional pilot or an entomologist spend thousands of dollars and hours of their time establishing climbs for no reward except the honor of a first ascent and the ability to name the route? Why, indeed, would anyone sacrifice what most Americans understand as the “American Dream” — a career, a house, and material wealth — to live in a tent or car, and have no permanent employment or discernable future goals?"

Posing these questions, climber Deborah Halbert forgets the extent to which climbing actually fits very well with the twenty-first-century “Dream,” no longer merely American since the end of the Cold War — not only in the sense that many climbers are professionals who do it for a living and get paid well enough to build wealth, but also insofar as today’s climbing body is more often than not presented as a convergence of the values of performance, speed and efficiency, in perfect compliance with fantasies of the individual who overcomes adversity and late capitalism’s demand for docile, transparent bodies.

The equating of climbing with success in business has been going on since at least the 1996 Everest disaster, during which eight people died on the mountain, including guides and officers from the Indo-Tibetan Border Police. The events of May 1996 were made famous by Jon Krakauer in his 1997 book Into Thin Air, and in the IMAX film Everest (1998). Scholars analyzing the media coverage of the event have described it as “the most widely publicized mountain- climbing disaster in history” and “the perfect story”, “a singular iconic subject that took on a life and meaning well beyond the circumstances that surrounded it,” something of a myth.

The 1996 disaster strengthened two things: the presence of the vicarious public, who could passively watch, discuss and judge the tragedy from the comforts of their living rooms, and a new framing of mountaineering as management. The belief that this disaster was a lesson in bad organization, team-work and shoddy management of personalities made it a favorite case study for corporate management education. Trainers and consultants still routinely appropriate the story to teach lessons in leadership and group dynamics.

But the logic that united climbing success with corporate success really blossomed when the third and final element entered the scene: the success of social and especially romantic relationships. That’s when climbing became synonymous with, more generally, the life worth living. And the 1996 Everest disaster was bookmarked by the releases of two Hollywood blockbuster films that had climbing as their backgrounds for suspense/action narratives: Cliffhanger (1993) and Vertical Limit (2000).

The films are shockingly similar in their narrative structures. Both begin with a dramatic rock-climbing fatality in which the male protagonist is implicated — he did what he thought was right, which resulted in someone falling horribly to their death. In both films, the protagonist responds to the tragedy by quitting climbing. And in both films, a situation unfolds that requires the protagonist to climb once more, to face the climbing challenge of his life, in order to save the life of a woman he loves. In Cliffhanger, that woman is our hero’s romantic partner, and in Vertical Limit, it’s his sister, but both films end with the final reward of a bright future in love. Climbing is winning at life and winning at life means happily ever after or “growing your relationship.”

Another decade later, the 2011 Citibank ad starring top pro rock climbers Katie Brown and Honnold as a couple on vacation performs this logic brilliantly, with a voiceover that directly satirizes the objects of older credit card ads (shoes, belts and engagement rings) and replaces them with the freedom that rock climbing ostensibly brings. “My boyfriend and I were going on vacation, so I used my Citi Thank You card to pick up some accessories.” The ad shows different kinds of climbing gear while her heavily vocal-fry-ed voiceover playfully lists them: “A new belt, some nylons, and... what girl wouldn’t need new shoes?” By now, the footage has cut to the “couple” climbing... “We talked about getting a diamond, but with all the thank you points I’ve been earning,” — and here, the rock music swells (“somebody left the gate open/come save us, a runaway train gone insane”) while spectacular drone footage makes clear that the “rock” in question is the one they are climbing.

While many pros like Honnold in fact built their careers while living out of cars and wholly rejecting a traditional life of work, credit-building and home equity, this ad performs a sleight of hand in which one forgets what the ad is for. The superimposing of climbing onto a credit line for a couple’s vacation creates a particular fantasy of what it takes to “have a life” today. Wealth-building and coupledom have become synonymous and they no longer appear compulsory, but as a glorious expression of freedom and human being itself.

.

More recent films continue to rely on the narrative structure in which “the climb” is both climbing and romantic love. One such example is The Climb (2017), a French romantic comedy which tells the true story of Nadir Dendoune, the first French-Algerian to summit Everest. Dendoune had no prior climbing experience, and made the attempt in order to prove himself to a woman he loves. Documentaries of important climbs repeat the same gesture. The Dawn Wall documents Tommy Caldwell’s romantic history alongside the historic climb, finishing with the triumph of his second marriage (this time, including a child) which aligns with his professional success. And while Free Solo is ostensibly built around the tension between Honnold’s real-life romantic relationship and his burning desire for El Cap — made spectacularly literal by the difference between the house the couple live in in Las Vegas and the van Honnold lives in when he is climbing — the film ends by reconciling this tension. Honnold’s climb is one glorious triumph across the board, as the girlfriend runs into the van and literally falls right into bed to welcome him back (not to mention that the couple tied the knot in 2020).

The more extreme mountain sports become, the more they are filmed, and the more these images are used to convince the vicarious public that to “grow your ___” is a universal, timeless human desire. Meanwhile, climbers continue to climb in pursuit of the very mountain thereness that unsustainable, bottomless economic growth continuously threatens.

* * *

In March 2020, both the Nepalese and Chinese governments announced that the 2020 climbing season was cancelled due to the Covid-19 outbreak. Though people have been calling for a closing of Everest for several years now, this is the first time that such a closure has happened.

In the midst of the ongoing pandemic, as the media constantly announced its “second wave,” Nepal reestablished international flights and announced a new climbing season starting in August 2020. Reports predict the 2020-21 season will be busier and more crowded than ever, given the backlog of climbers who missed out the year before. But the temporary closure is a reminder that closures — even of mountains as lucrative as Everest — are possible. What if Everest went the way of Uluru and were closed to climbers forever?

Such a move would be more complicated than it appears, and the complications are dramatically different for the different communities it would affect. The loudest protests would undoubtedly come from climbers themselves — but not the most skilled ones, who already have access to, and in many cases more interest in, the less frequented Himalayan peaks. On the contrary, if the “Everest selfie” phenomenon is any indication, the greatest emotional impact would be on climbers for whom Everest is the best or only Himalayan opportunity.

Correspondingly, however, the greatest economic impact would be on the local Sherpa support economy that has been built around Everest. Sherpas are pro climbers in the truest sense — paid to guide others into the world of Everest — and many of them die while doing their job. Any moves to permanently close off the summit or dramatically lower the number of permits issued each year would have to seriously consider the effect on Sherpa communities, currently engaged in their own debates about their future as climbers. Large-scale relocations might be undertaken, as if a natural disaster had occurred.

In a sense, though, a natural disaster is precisely what has already happened. This disaster consists not just of the traffic jam at the top or the high death count. It encompasses a vulnerable mountain environment that has ballooned with economic growth. Due to climate change, the Himalaya could lose more than a third of their glaciers by the end of the century. This could have devastating consequences for the 1.65 billion people living in the mountains and in downstream countries, who are at risk of flooding and the destruction of crops. Between Himalayan warming (growth at its most abstract and hardest to mitigate) and the “zoo” and “garbage dump” on Everest (growth at its most obvious and tangible), the scale and complexity of the recent damage to the region is only now beginning to come into view. Everest is living proof, if you will, that the limits of human desire for the good life have finally reached “the top,” the limits of what the world can handle. Ironically, it has taken some of the best climbers to bring this to the world’s attention.

* * *

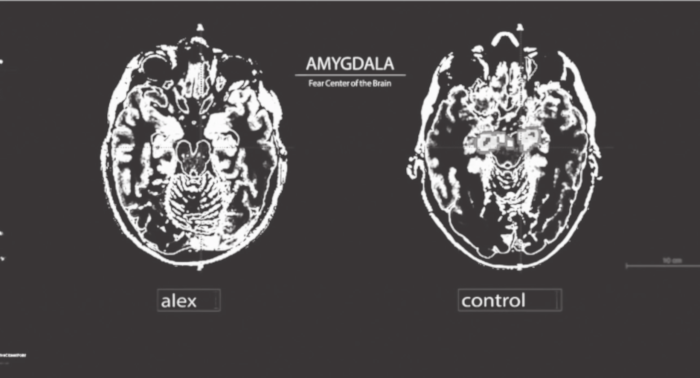

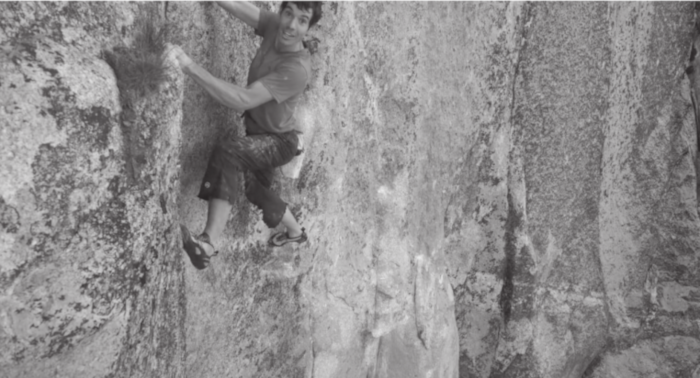

Honnold himself is very much the embodiment of the mythologized climber who doesn’t quit, sacrificing anything to achieve his goal. In Free Solo, his task is presented as his alone — in ongoing tension with the rest of his life, which involves other people (most notably his girlfriend), middle-class suburban stability (buying and furnishing a home), and even the documentary film crew following him. Everyone close to Honnold worries that the cameras will distract him or make him act recklessly, so the crew members go to great lengths to obscure themselves as much as possible. At the moment of the historic climb, the camera operators have to update one another on Honnold’s location over walkie-talkies, because he is continuously ahead of where they think he is, literally outrunning the cameras.

Free Solo is exhilarating because it captures that thing that has given meaning to summiting the Himalaya over the past century. It’s the thing that continues to outrun the cameras and that propels both the climber and the film itself forward, inch by inch up the sheer granite, in pursuit of something authentic. This is what the most important first ascents do: They open up the magic of the mountains to the audience watching from home. But the lesson of Everest is that such an inspiring space doesn’t stay open forever. Like everything else precious, it is not an infinitely renewable resource.

That mountains get used up materially is not news. But environmental degradation isn’t just material; it’s also cultural. The cultural meaning of environments is another “resource” humans use up. If there is anything still outrunning the gaping maw of capitalist cooptation, it’s what Roberts calls “the ‘in’-ness of climbing — its temporary establishment of an anarchistic utopia of common purpose.” But even this anarchistic utopia is increasingly endangered, and in a complicated relationship with its own mediation and commodification. We want the climbers to win, to escape unscathed into the glorious wilderness — but we also want to watch, because this is clearly a close race. It remains to be seen whether both demands can indeed be met. It also remains to be seen whether we can really still talk meaningfully about climbers’ common purpose.

* * *

Climbing Technotopia, or: Did Free Solo Really Happen?

In the most literal sense, Everest is not the world’s highest mountain. It is the highest mountain only for this particular simian climbing animal, Homo sapiens, with its particular, limited perspective on the world. Everest is the highest point on terrestrial Earth, but the highest mountain is Hawaii’s Mauna Kea, measuring 10,200 meters from its peak down to its base at the bottom of the Pacific. And while this may seem like a frivolous thing to point out — since no mountaineer today cares — climbing culture registered this in 1945, when Jacques Cousteau founded something called The Club of Underwater Alpinism.

Perhaps Cousteau had in mind the mountains in the ocean, called seamounts, which divers can literally ascend, clinging to them in a way that looks a bit like climbing. Given his life’s commitment to what later became known as SCUBA, however, he certainly had in mind the shared imaginaries between climbing the highest heights and diving to the deepest depths, both of which require oxygen and other support of basic life functions. In 1943 Cousteau and Émile Gagnan completed development of the first open-circuit SCUBA system, called the Aqua- Lung, after which Cousteau famously went on to become the great pioneer of popularizing underwater imagery and diving-as-discovery. But his first framework for thinking about humans in the ocean was climbing. It’s as if people always knew that humans couldn’t survive in mountain environments without major technological interventions.

To say that climbing and technology have a long, ongoing love affair is not to say that climbers love relying on technologies. On the contrary — they often push this fact under the rug, in order to foreground the enormous work the body must do in order to climb, especially at altitude. The love affair between climbing and technology is more abstract and complicated. It is at once literal and analogical. It has to do with their shared imaginaries of speed, breaking records and always reaching for more.

In 2023, Poland is set to simultaneously open two new centers in the city of Katowice: a Center for Scientific Research and the first ever Center for Polish Himalaism, a mountaineering museum commemorating the achievements of Polish climbers. The museum’s name holds a redundancy: himalaizm is the Polish neologism to describe the Himalayan mountaineering for which Polish climbers are famous. The word distinguishes the achievements of Poles from those of other Europeans, who are happy to call themselves alpinists regardless of where they climb. The press release announcing the centers’ simultaneous openings states that climbing is about superlativity (the highest mountains = the greatest achievements), and is intimately connected to constant and speedy advances in science and especially technology. The climbing body is itself a contested site for technological imaginaries, suspended somewhere between its prehuman origins and its posthuman future. Paleoanthropologists argue contentiously over the role of climbing in hominid evolution, examining the various possibilities for reading the histories of arborealism and terrestrial bipedalism in early hunter-gatherers. A new bioinspired climbing robot currently in progress, created by a team at the University of Genoa, is modeled on primate locomotion, because primates — all different kinds, from macaques to chimps — are the fastest and most efficient animals at climbing.

This futuristic climbing body includes new visualizing technologies, which expand the climbing universe on multiple levels, from what the vicarious public can see while following climbing achievements from home, to helping climbers plan new routes, to recovering lost bodies. There’s Nat Geo’s new “Everest From Above,” which uses drone technology to visualize an interactive view from Everest in 360 degrees. Renan Ozturk (one of the stars of Meru, Jimmy Chin and Elizabeth Vasarhelyi’s 2015 film), created it using drones operated from Camp 1, partly in an effort to recover the body of Andrew Irvine. There’s also the El Cap Gigapixel project, created for climbers to find new routes with the help of unprecedented image resolution which allows for deep zooming in.6 The NYT feature about it allows users to explore the exact route of Tommy Caldwell and Kevin Jorgeson’s Dawn Wall climb. Such projects promise a future of ever higher resolution and ever “better” vision, echoing the promise of climbing itself.

Meanwhile, in every physical respect, the liminal character of climbing — especially obvious at high altitudes, where the human body is constantly on the verge of its physiological efficiency — makes it a theater for the limits of the human and presages the coming stage of human development. This is especially obvious — and literal — in the recent growth of paraclimbing, where technologies are invented and developed (often by elite climbers with impairments, who know their bodies and the needs of their climbing craft better than anyone else) in order to provide access for athletes with disabilities to compete in climbing events. Because many paraclimbers rely on prosthetics and bionics, it’s increasingly common to hear that they are better climbers than those without such enhancements, able to do things with bionic feet and fingers and limbs that would otherwise be too painful or difficult. “Access” here becomes not just what’s already accessible to non-disabled climbers, but opens the imagination to everything beyond what people think “the body” can do.

Hugh Herr heads the biomechatronics group at the MIT Media Lab, creating bionic limbs that emulate the function of natural limbs. Herr is not only a groundbreaking engineer, but also an elite climber since his youth, when an expedition caused both of his feet to have to be amputated six inches below the knee. In interviews, he often mentions that his own climbing is stronger because of his prostheses, and is a fervent defender of augmentation in general, in the name of optimization.

.

Importantly, however, Herr’s definition of optimization is not limited to physical performance, but invokes a broader vision of a better world and more just social relations. The key is for bionics to actually serve social diversity, empathy and happiness. Herr’s is a techno-topia straight out of cyberpunk, but not only because bionics might remind us of robots. Like all good cyberpunk, bionics grapples with the complexity of modern society.

In contrast, Honnold’s is a utopia of an accelerated Vitruvian Man, of minimalism, solitude and unadulterated doing-whatever-the-fuck-one-wants. Free Solo presents unplugged, off-grid climbing — and living — as the quintessential form of human freedom. The sheer simplicity of how Honnold does what he does, coupled with his ascetic lifestyle and reserved manner, makes him seem like he’s from another time. And yet, watching Honnold climb El Cap, there is no mistaking its futuristic flavor. Like all his free climbs over the past decade, it’s stunning because it seems impossible for a human body (and mind) to do.

Though both are distinctly future-oriented and present climbing as, at bottom, a form of futurism, these two visions of the future couldn’t be more different. While Herr’s bionics shows that projects that have human freedom as a goal must take seriously that bodies accomplish what they accomplish within social contexts, Free Solo’s vision of freedom is freedom from social context.

Even prior to El Cap and already the greatest free solo climber in history, Honnold was fond of saying that the key to climbing is knowing when to quit — in the small sense, as in knowing when to go home for the day, but also in the larger sense, as in knowing when to stop altogether. This is the only way to survive a sport that is bound to kill you, sooner or later. Quitting is at the heart of the film’s happy ending, as Honnold looks squarely into the camera and announces, less than convincingly, that the next climbing achievement on that scale (but “bigger, cooler”) will be by “some kid” and probably not himself.

In extreme sports, the phenomenon of continuously extending the limit of the possible is called “progression,” when someone outdoes the last impossible accomplishment by doing something “bigger, cooler.” Extreme athletes themselves have been critical of progression as a dangerous ideology. Steph Davis, a pro rock climber and one of the top female wingsuit BASE jumpers in the world, strongly argues against it: “Perhaps progression means something very different. Perhaps it means refining the experience, becoming safer, more elegant and more aware. Perhaps it means sustainability.” Or, perhaps sustainable climbing is about the fragility of not only environments, but also of dreams, risks, desires. Perhaps climbers themselves are to be sustained.

.

And yet the public swoons over the perceived madness of climbers, their refusal to stop, even in the face of enormous risks. The climber who keeps climbing is the one who upholds the public’s expectation of what motivates the activity in the first place, i.e., unstoppable, bottomless passion. When climbers fall to their deaths, which recently happened to another superstar of the sport, speed climber Ueli Steck, the public response is equal parts what did you expect? — as in the title of a New York Times opinion piece, “How Ueli Steck Met Mountaineering’s Oldest Companion: Tragedy” — and shocked disbelief — Steck’s body was autopsied, as if it weren’t possible that he might simply have slipped and fallen. Likewise, the two speed climbers who fell from El Cap in 2018 caused a media flurry of speculations of “overconfidence, miscommunication, and complacency,” as if falling while speed climbing could only result from error.

Honnold himself is a great example of a climber who has achieved what he has precisely because he didn’t stop while ahead. In one oft-quoted piece of footage from an earlier film, of his soloing of Half Dome in 2011, he is momentarily paralyzed with fear on a ledge, so much so that he cannot move — forward or back — or even explain what’s happening to him. The film then cuts to him climbing happily to the top despite this minor setback. The whole premise of Free Solo is that to free solo El Cap is pure madness, to which everyone repeatedly attests, including his girlfriend (“it’s hard for me to grasp why he wants this”) and the other pro climbers in the film (Tommy Caldwell calls climbing with Honnold a vice, “like smoking cigarettes,” and describes him as “the most likely to die”). As the film’s co-director and fellow climber Jimmy Chin ominously intones, “if you keep pushing the edge, eventually you find the edge.”

Except that Honnold doesn’t. That’s the big take-away. Beneath Free Solo’s finger-wagging about quitting while one is ahead, including a discussion of Steck’s untimely death, flows a torrent of unstoppable passion to keep pushing the edge.

* * *

But this bottomless human drive doesn’t exist in a vacuum. It meets its match in the bottomless recalcitrance of the mountains. It’s only together that they constitute the experience of meaning for which so many humans say they climb. In other words, if the climber’s desire is more than human, this is not only because it invokes bodies beyond human bodies but because it’s also always embedded in a particular environment. The so-called limits of the human body are never just bodily or just human — they always have terroir, if you will, an environment in which what is possible must always be carefully negotiated.16 Free soloists may be free of society, but they are not free of everything.

Furthermore, this terroir itself is not merely geographical or material; it’s also cultural. The environments in question are impacted by culture and have impact on culture. They are imagined in particular ways. Their cultural meanings, just as much as their physical characteristics, shape what is and is not possible, and what in time becomes possible — in culture and imagination but also somatically, materially and in fact. Desire, bodily limits and environmental recalcitrance are inseparable from one another. It’s not only elite athletes that make progression possible; the physical world from which they demand it makes it possible as well.

BASE jumping is illegal in all US national parks. Those who argue for legalizing it do so on the grounds that the constraints on jumping, not the jumps themselves, are causing the deaths. They also like to point out that, unlike many other activities that parks allow, BASE has almost no environmental impact. But if desire has terroir, this means that we are no longer just talking about climbing environments. The terroir is not only that of climbing, but of progression itself. And this means that the impact is greater than just the physical impact of climbing tourism.

Critics of progression have long known that the ever- growing pressure to use the camera is at least partly to blame, and indeed, BASE, where today almost no one jumps without their GoPro, seems especially troubling in this respect. Philosopher Jean Baudrillard had his doubts about this aspect of mountaineering back in 1988, claiming that such practices effectively exhaust their own meanings because they are preprogrammed to succeed before they happen. It would never occur to anyone to attempt to climb unless they had decided ahead of time that it was, in fact, possible. Thus, when these ostensibly shocking ascents finally take place, they are, culturally speaking, “of no consequence.” He equates the Himalayan summits with the moon landing, which, he writes, has not revived the dream of conquering space but exhausted it.

Of course, it’s counterintuitive to describe Honnold’s achievement as being of no consequence. But Baudrillard’s point is not about the effort, talent, work and sacrifice required, but about the cultural meaning of the achievement. The free-climb of El Cap — which Honnold describes as “the center of the rock-climbing universe,” apropos of space dreams — was culturally preprogrammed to succeed, and no one knows this better than climbers themselves. When Steck broke the record speed for climbing the Eiger North Face (for the second time), he seemed very happy, to be sure, but not the least bit surprised. Nor would it surprise him if that record were promptly broken by someone else, as he explains immediately after breaking his own record, still wiping his very runny nose. It’s simply inevitable.

Honnold, too, almost immediately following his victory, predicts that someone will soon outdo him. And this, on top of the fact that Free Solo is the first time such a massive mountaineering achievement has been filmed in real time, thus creates the uncanny experience of a film premised on the question Will he make it? — down to the nail-biting finale — when, in fact, everyone watching knows that Honnold did indeed make it.

.

The experience of watching Honnold look squarely into the camera and announce that he “made it,” recalls a passage from “The Public Climber” by Roberts in which he says that climbing that’s recorded for a public is “not the real thing”: Television executives may salivate over the prospect of a live broadcast from the summit of Everest, but I don’t know many climbers who would miss a good party to catch the show. For much the same reason, I suspect climbers as a group have for the most part remained unmoved by the space shuttle and the moon shots. The premeditated self- consciousness of Neil Armstrong’s announcing his Giant Step for Mankind at the moment he performed it prevents our belief in it. It’s not that we don’t believe that Honnold did what he did. It’s that watching it happen precludes witnessing the game- changing moment as game-changing, in its immediacy, or as what some philosophers have called an event. It’s always something that has already happened, something in the past, and so, ironically, as an audience we miss out on it, on the now-ness and raw-ness of it, precisely as we watch. Seeing it — on camera — never makes it true.

In the end, Roberts sounds resigned to the “anthropological irreversibility about climbing’s drift toward entertainment,” and makes clear that he knows that “today’s Everest’s expedition cannot be carried out with quite the unself-conscious zest exemplified by the 1924 expedition.” In other words, there’s no putting the genie back in the bottle and returning climbers and their publics to the feelings that motivated Mallory. And yet, all of his essays end on the note that climbing’s reward is precisely in that zest, that thing in the climbing body that cannot be reduced to pithy explanations or consumed by hungry spectators.

- Margret Grebowicz

Excerpts from Mountains and Desire.

Climbing vs. the End of the World

(Repeater, 2021)